Download Full text PDF version Here

Authors: Raymond A. Levy and Milton Kotelchuck

1 Introduction

Fatherhood as a positive and critically important topic has not been taken seriously in academia, health communities, obstetrical clinical practice, social policy or business until recent decades, despite the publications of Kotelchuck et al.,[18] Kotelchuck [14], Lamb [22], Lamb and Lamb [24] and others starting in the 1970s. President Barack Obama initiated a federal program, My Brother’s Keeper[28], which helped to generate credibility for the importance of fatherhood. Now, in the public-health, federal funding, and research worlds, more attention is being paid to fathers as a central component of family life, including their frontline parenting functions, in addition to their economic contribution to children and families. However, it still remains true that little attention has been paid to fathers in prenatal care, the emphasis of this chapter.

This chapter presents and discusses the results of two combined waves of Father Surveys conducted by The Fatherhood Project[19][20] during prenatal care visits at the Vincent Obstetrics Department at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. This study’s survey of 959 fathers accom panying their wives and partners for prenatal care at a large urban tertiary hospital system, we believe, is the largest sample to date of direct men’s voices on their prenatal experiences, condition and preparedness. The results are followed by a targeted discussion of practice implications to increase men’s involvement during prenatal care and to make pregnancy and birth a healthier, more family-oriented event.

We began by exploring men’s voices and perspectives in prenatal care, as early in the family life course as practically possible, and we hoped that their voices might lead to enhanced clinical care. First, we present a more detailed history of the treatment of men in prenatal care within academic and service provision circles to further justify the importance of this study.

1.1 History of Men and Prenatal Care

There is a substantial and growing literature documenting that increased father involvement during the perinatal period is important for healthier births[15], healthier infants and children[39], healthier families and partners, as well as healthier men themselves.[9][17] The broader Maternal and Child Health (MCH) life course and preconception health professional communities in the U.S. encourage early and continuous paternal involvement in the parenting process,[17] as do national federal family and social policies and community-based fatherhood initiatives.[1]

The course of prenatal care services is an important time in the pregnancy and birthing period, and conceptually a possibly important period for paternal involvement and development.[16] Yet pregnancy and birth are not usually conceptualized as a father-inclusive family event. Obstetric and prenatal care services are seen primarily as women’s or mother’s domains as reflected in the names of our fields of study and care (Maternal and Child Health, Maternal Fetal Medicine; Obstetrics as women’s primary health care.)

Despite these negative factors, there is a changing reproductive health services reality on the ground; men are increasingly presenting for prenatal care and ultra sound visits, and now nearly 90% join their partners in the labor and delivery room[31][32] and are increasingly eligible for, and using, post-partum paternal leave (In the U.S., seven states and Washington DC now have paid family leave). Fathers are increasingly welcomed into pediatric practice as well[39].

These may in part reflect the evolving transitions from men’s and women’s traditional prescribed gender-based parental roles to more shared and equitable parental roles, with men assuming more engagement with infant care responsibilities.[15] Yet existing programmatic and policy promotion efforts to encourage this transformation in the U.S. seem weak and underdeveloped—and especially not focused on the pre-birth roots of fatherhood.

Moreover, there is very limited prenatal attention to men’s own health or devel opment as a father, his generativity.[17][9][16] Paternal engagement and commitment don’t just begin at birth; fatherhood, like motherhood, may be a developmental stage of life and health.[16] Yet current understanding of the impact of pregnancy experi ences on men’s health and family health as well as the impact of contemporary institutional practices on men’s own health development are critical under-studied topics.

Men’s voices and perspectives in the prenatal period are too rarely assessed and are generally missing from the Maternal and Child Health literature,[9][10] limiting knowledge about their potential needs, perceptions, contributions, and involvement. Fathers are often discouraged from involvement with MCH-related services and sometimes assumed to be uninterested.[37][6] This data could provide an important basis for enhanced national and local father-friendly clinical practices. The earlier men are involved with their infants, the more likely they are to remain involved[32] and the more likely their involvement will yield improved family outcomes.[35]

1.2 Aims

This research study has six goals:

- To learn about men’s paternal involvement, needs, and concerns during the time of prenatal care appointments

- To learn the status of men’s health and mental health in the prenatal period

- To assess how fathers were treated by the Massachusetts General Hospital Obstetrics staff during their partners’ prenatal care visit for quality improvement purposes

- To learn what additional fatherhood information and skills they might like to acquire and through what formats and modalities

- To learn how men feel about the fatherhood study and potential fatherhood prenatal care initiative

- And finally, to discuss the implications of the results and offer practical recom mendations for improved prenatal care and obstetric practice, to ensure earlier and enhanced paternal involvement

2 Methodology

2.1 Sample

The target sample for each of the two 2-week, cross-sectional cohort study waves were all men attending prenatal services, including ultrasound, with their partners at the Obstetric Services of Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), a large urban tertiary hospital system in Boston, Massachusetts with multiple community health centers (CHC) and offsite satellite clinics. The MGH Obstetric Services operates as a single hospital-wide practice, with centralized ultrasound, Maternal-Fetal Medicine specialty and delivery services, and approximately 3200+ births per year. Subjects were recruited at the central MGH prenatal clinic and at two of its major CHCs, in Chelsea and Revere, which serve communities with disproportionately large immi grant populations. The study took place during the first 2 weeks of August 2015 and the first 3 of September 2016. MGH Obstetrics sees approximately 100 prenatal care and ultrasound appointments daily.

2.2 Recruitment Methodology

When fathers arrived in the prenatal care waiting room accompanying their partners to prenatal medical visits, they were approached by one of the study’s research assistants or primary investigators and told about the voluntary, anonymous father hood study. They were then asked if they were willing to participate, and if so, take the fatherhood survey immediately, with no rewards offered for participation. If they agreed, they were given a mini-iPad tablet computer on which to complete the survey. If they preferred not to participate or could not be engaged in the recruitment efforts, they were not asked a second time.

2.3 Survey Instrument and Survey Collection Methodology

The fatherhood survey was developed by the researchers associated with The Fatherhood Project at MGH[25] The survey instrument was a 15–20 min self-administered survey. It was composed of a series of closed-ended questions with an opportunity for open-ended comments at the end. It was available in multiple languages—English, Spanish, and Arabic in 2015; and also Portuguese and Serbian in 2016. The survey was formally reviewed and approved by the MGH Internal Review Board.

The survey, completed in the prenatal waiting room, was composed of two sections: prior to the prenatal clinical visit, the survey questions addressed broad fatherhood issues including paternal preparation and engagement, needs and concerns, and their physical and mental health status. After the prenatal visit, the survey questions assessed the men’s immediate prenatal care treatment experiences, their needs and desires for additional fatherhood information, their preferences for how that information should be delivered, and their assessment of the MGH father hood study and potential initiative.

A paper copy of the survey was offered to those unable to complete it electron ically in the waiting area, 14 in total. All iPad survey data was transferred electron ically to an online data system for analysis at the time of completion.

The survey instruments and recruitment procedures were very similar across the two waves of data collection. There were however some minor differences from the first to the second wave: Subjects information was now also collected at two MGH-affiliated community health centers—Chelsea and Revere Health Centers— in addition to the main MGH Obstetrics hospital campus. There were some minor edits in the survey instrument to improve clarity and response options, and some additional questions added on father’s roles, emotions, and attitudes. And the survey was also available in additional languages as described above.

2.4 Analysis

For this chapter, the results of the two waves of data collection are combined for analysis. Prior data analyses (not presented) had demonstrated a remarkable degree of similarity of responses across the two administrations of the survey, and we therefore combined them to obtain a larger single sample size. We further only examine those questions here that the two surveys had in common, the overwhelm ing majority of the survey items.

This study utilizes standard descriptive statistics to examine the overall findings. The results for each of the study aims will be presented in turn, immediately followed by a commentary on their meaning.

2.5 Methodologic Limitations

While we believe this study provides a successful methodologic framework for assessing father’s voices and experiences during the prenatal care period, we also recognize that this study has some limitations, especially around its study sample, that may restrict its full generalizability.

Specifically, first, the study sample is not fully representative of all men during the prenatal period; it is a convenience sample from a single urban tertiary hospital in Boston, MA—a state and region with a slightly higher SES population, less racial diversity, and more immigrants than the U.S. as a whole. Second, and probably most significant, this survey represents only those fathers who chose to accompany their partners to MGH Obstetric prenatal services during the study periods. While we estimated that we had surveyed a broad and substantial proportion (43–46%) of all potential male partners (data not included), we obviously cannot ascertain the opinions of the non-attendees. Third, the prenatal policies and practices of the MGH Obstetric Services that the fathers experienced and assessed may not be representative of all prenatal practices in the U.S.

And finally, fathers are a very heterogeneous population; responses were explored across a wide variety of sub-populations, but given the complexity of the analyses and findings, this specialized line of research was not more actively pursued for this chapter.

In sum, despite the limitations noted above, this study succeeded in obtaining the perspectives and voices of a very large and broad cross-sectional sample of fathers during the prenatal period. The study provides for important initial baseline esti mates of paternal topics heretofore under-studied.

3 Results and Results Discussion

Sample: The final sample of fathers who provided data during the two waves of data collection was N ¼ 959. All men accompanying a woman into the prenatal care waiting room (N ¼ 1412) were approached. One thousand one hundred seven fathers were eligible for the study; 959 provided data on the first part of the survey and 899 provided complete survey data, including 14 fathers who mailed in the second half of their survey. Overall, the study achieved a very high acceptance rate: 86.6% of eligible fathers (959/1107) participated in the survey, with only 148 fathers (13.4%) not providing answers to the survey, including 69 (6.2%) who formally declined.

Men who were not eligible included those whose partners were receiving non-prenatal care OB/GYN services, such as pre- or post-partum fertility or genetics counseling or post-partum follow-up care; those who had filled out the survey at a previous visit during the study period; and those who were not the father.

Given that this was an anonymous, voluntary survey, we were unable to system atically record the specific reasons for non-participation or the men’s or their partner’s demographic characteristics. Informally, we noted reasons varied from being too busy on a cell phone call, language issues, not wanting to be distracted from the primary maternal focus of the visit, late arrivals, child caretaking, or simply no explanation given.

Additionally, we have no knowledge about the fathers who did not come with their partners for prenatal care; nor were we able to ascertain the characteristics of women who came without a male partner or had no male partners.

3.1 Study Population Characteristics

3.1.1 Results

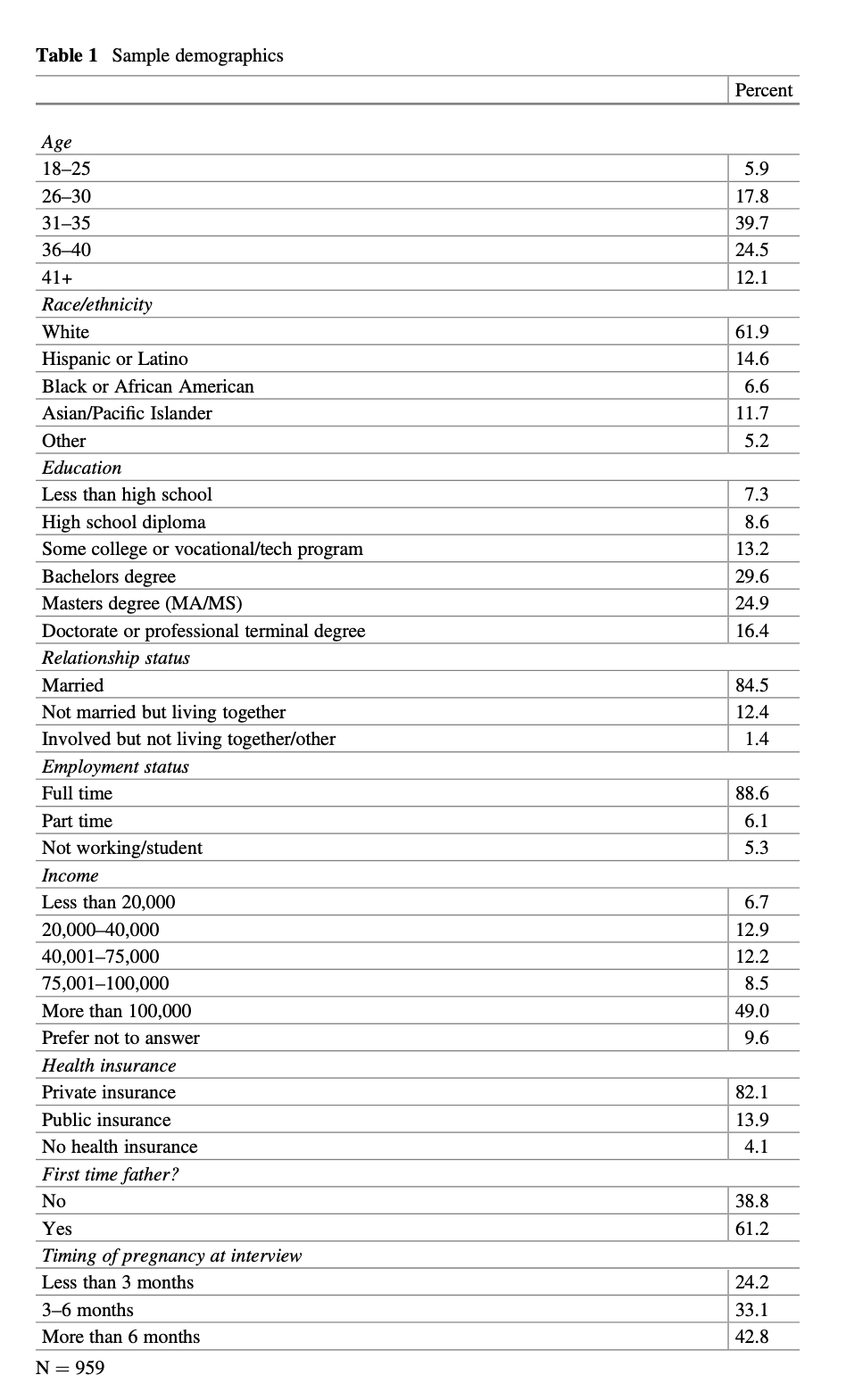

The majority of study fathers (76.3%) were over 30 years of age, with fathers 31–35 (39.7%) and 36–40 years old (24.5%) the larger age groups. Our cohort was slightly older than the overall Massachusetts fatherhood births population; with 68.3% above 30 years old, 34.4% 31–35 years old and 21.5% 36–40 years old. Relatively few fathers were either younger or older. (calculated from Massachusetts Department of Public Health 2018[27])

The majority (61.9%) of the study participants were White, with 11.7% Asian fathers, 14.6% Hispanic fathers, and 6.6% Black fathers; relatively similar to the overall Massachusetts birth population (59.5%; 9.3% 18.4%; 9.9% respectively; calculated from Massachusetts Department of Public Health 2018[27]).

The study fathers were well-educated: 41.3% had a post-BA degree and only 15.9% had high school or less education. The vast majority were married (84.5%), worked full-time (88.6%) and had private insurance (82.1%). Fewer MGH fathers (13.9%) utilized Medicaid than the overall state birth population (33.7%; calculated from Massachusetts Department of Public Health 2018[27]) (Table 1).

The majority of study participants were disproportionately first-time fathers (61.2%), much higher than Massachusetts fathers in general (45.0%). While there was good representation across the trimesters of pregnancy when fathers were surveyed, the sample skewed slightly toward older gestational ages.

Overall, the surveyed fathers attending prenatal care visits at MGH Obstetrics are a diverse population that skewed towards older, higher socioeconomic status (SES) and first-time father populations, though racially and ethnically similar to all Mas sachusetts births.

3.2 Fatherhood Preparation and Engagementin Reproductive Health Services

3.2.1 Results

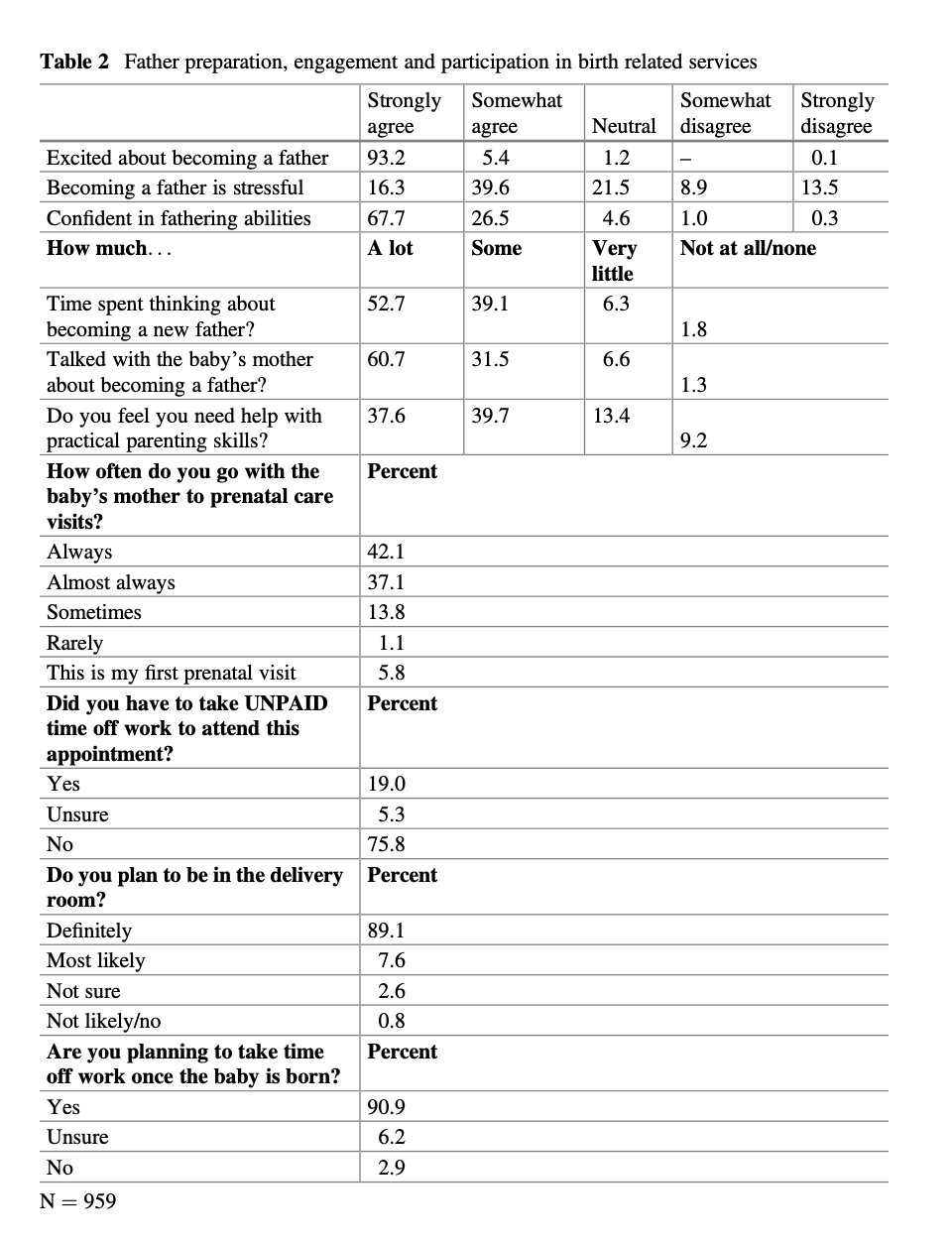

First, the survey reveals that the prenatal period is a time of active engagement and joy for men as they are becoming fathers and creating families, a potentially transformative period in men’s development. Over 98% of fathers say they are excited about becoming a father, 93.2% very excited, and almost 92% have spent time thinking about their emerging fatherhood, 57.2% a lot. Over 92% of expectant fathers have spoken with their partner or wife about becoming a father (60.7% a lot, and only 8% little or no time). And over 90% of the fathers plan to be in the delivery room and take time off after the birth of their child. Second, the fathers express a balance of general confidence and a recognition of needing more knowledge and practical fatherhood caretaking skills. While 94% say they are confident in their

fathering abilities (37.6% agree and 39.7% somewhat agree), it is also true that the fathers are asking for either a lot or some help with practical parenting skills (77.3%). Third, fathers demonstrate high levels of involvement in their partner’s prenatal care and future delivery health services. In our sample, fathers always or almost always (79.2%) accompany their partners or wives to prenatal visits and another 13% sometimes attend. And 19% of fathers took unpaid time off work to attend this study prenatal visit (Table 2).

3.2.2 Results Discussion

Our study findings on father’s involvement in maternal reproductive health ser vices—ultrasound visits, PNC, and delivery attendance expectations—is consistent to what others have also reported about fathers’ increasing presence for ultrasound and delivery.[31][32]

The strong and consistent involvement of fathers with their wives and partners in prenatal care reflects their interest in active fatherhood, from thinking about and discussing impending fatherhood with partners to attending prenatal visits, taking unpaid time off work and being in the delivery room. Fathers’ interest establishes the foundation for an increase of paternal services and attention in prenatal care, which we elaborate on further in the Recommendations section.

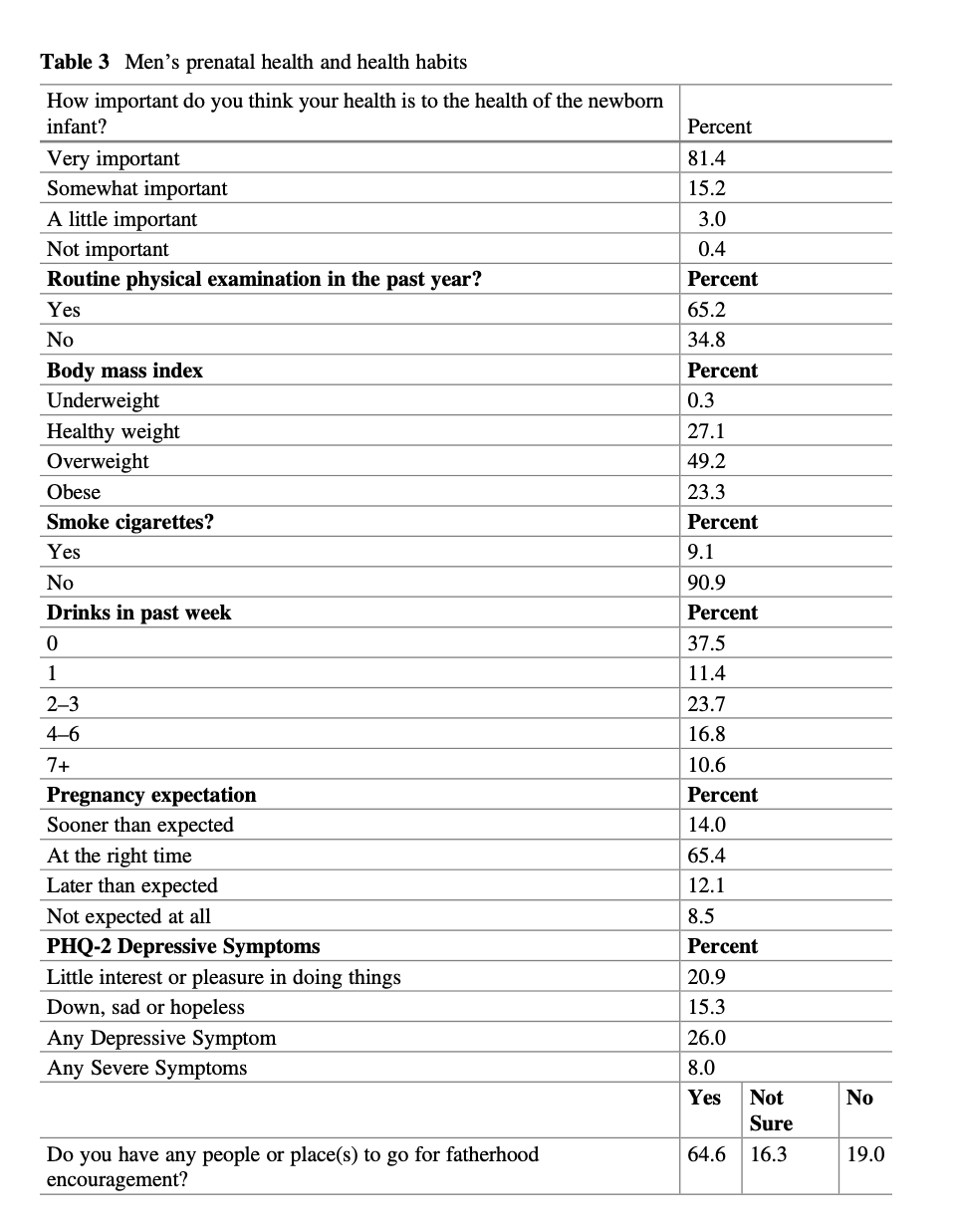

3.3 Father’s Health, Health Care and Mental Health 3.3.1 Health and Health Care

Results

The vast majority of fathers profess an awareness of the importance (81.4% feel it is very important) of their health for the health of the newborn infant (15.2% feel it is somewhat important). However, despite this awareness, only 65.2% of fathers had a routine physician exam in the past year. Second, fathers coming to prenatal care visits were substantially overweight (49%) or obese (23%). These figures appear to be consistent with men’s elevated BMIs in the U.S. Third, excessive substance use was relatively uncommon in this sample of fathers, though possibly under-reported.

Smoking was much less common (9.1%) than drinking (62.5%) with 16.8% of men reporting 4 or more alcohol drinks per week and 10.6% men reporting 7 or more drinks per week. Fourth, 65.4% of pregnancies in this sample occurred at “the right time,” a potential indicator of good family planning. Still 14.0% of pregnancies occurred sooner than expected and 8.5% were not expected at all (Table 3).

Results Discussion

Overall, the survey findings suggest that fathers have substantial health and health service utilization needs during the prenatal period, reinforcing sporadic similar reports of men’s poor health and service needs pre-conceptually.[8][4]

The study results should reinforce the emerging interest in encouraging men to attend to their own preconception and prenatal health care,[17][9][3] in order to enhance his own life course health, as well as to his infant and partner’s well-being.[15] That almost 35% of men have not had a routine physical exam in the past year is a missed opportunity to have a pre-birth check-up and learn about and address any existing, significant health issues.

3.3.2 Mental Health

Results

Although virtually all fathers in our study experience joy in the pregnancy period (98.6%), our findings show a significant presence of depressive symptoms as well. The survey’s PHQ-2 two question screener (Kroenke et al. 2003) yielded findings worthy of concern. Over 21% (21.4%) of fathers said they find little interest or pleasure in doing things while 15.5% described themselves as down, sad, or hopeless. In total, 26% of fathers endorsed one or more of these two symptoms, while 8% described themselves as having severe depressive symptoms as measured by at least one of the symptoms occurring more than half the time. At any given time in the US, 7.2% of adults are diagnosed with depression (SAMHSA 2019), which might suggest that our sample of fathers in the prenatal period have higher rates than average. The study also found that over 35% of men don’t have, or are uncertain about having, people and places to go to for fatherhood encouragement, potentially suggesting a feeling of isolation at a critical period of emotional vulnerability.

In addition, 56% of fathers endorsed the statement that the pregnancy period was a source of stress. Analyses using only our 2016 study participants (Levy et al. 2017), where we had explored the sources of the paternal stress more deeply, showed the concerns were focused on financial pressure (44%), the ability to care for the baby (29%), decreased time for oneself (20%), and the changing relationship with the mother (15%) (Data not presented in the tables). Additionally, a group of men (15%) were worried that they would repeat the mistakes of their father, mistakes that they likely experienced in their own development, perhaps abuse, neglect or absence at their most extreme.

Results Discussion

Our data reveals that the prenatal period is marked by substantial mental health needs for the majority of fathers. Entering and negotiating the unknown world of preg nancy and prenatal services can contribute to men feeling insecure and uncertain about expectations.

Joy: The overwhelming majority of men are trying hard to meet the challenges and are experiencing the joys of fatherhood. We observe men embracing their newfound fatherhood role as an opportunity for growth, for the realization of long held dreams and the healing of past disappointments and even traumas. Others see fatherhood as an opportunity for increased capacity to love and for the expansion of identity, a discovery of a previously unexpressed part of the self.

Stress: The current survey findings of elevated levels of prenatal paternal stress are consistent with other research, which similarly has noted greater stress among new fathers (Philpott et al. 2017; Gemayel et al. 2018). One’s circle of concern needs to expand to include the welfare of the new baby; and one needs to derive gratifi cation from the sacrifices for and pleasures of another. These psychological chal lenges are welcome for many, daunting for some, and insurmountable for others.

Additionally, the fathers are facing practical financial and childcare demands that can be challenging. There are financial pressures, changes in the demands of work life balance, and less time availability to enjoy the marital or partner relationship (Kotelchuck 2021b).

Isolation: In this study sample, over 35% of men don’t have or are uncertain about having people and places to go for fatherhood encouragement. Other paternal mental health researchers have also noted that fathers often feel isolated during the prenatal period, and that paternal isolation is a risk factor for pre- and postpartum depression and anxiety (Gameyal et al. 2018). With major changes to fathers’ lives, additional social supports can be helpful.

Depression: This study’s finding that 26% of fathers endorsed one of two depressive symptoms adds to the growing literature about men and depression during the perinatal period (Paulson and Bazemore 2010). Using our 2016 data (Levy et al. 2017), we found that elevated paternal stress, both overall and by specific source, was significantly associated with the father’s depressive symptoms. This finding suggests that fathers can be overwhelmed by the stresses of impending fatherhood, and they often struggle to master the internal and practical demands. The finding that 26% of the fathers endorsed one or both of the depression items on the PHQ-2 in our study does not confirm a diagnosis of clinical depression, although it certainly does indicate that further evaluation is warranted.

Currently, there appears to be little professional awareness about this level of stress and depression in fathers during the prenatal period. Of critical importance, some men who won’t allow themselves to ask for help externalize their problems and become angry, blaming friends, loved ones or society (Rowan 2016) and use sub stances to self-medicate, although curiously our sample seems relatively free of this phenomenon. Psychological evaluation of fathers in the prenatal period, when men clearly have mental health stresses while feeling vulnerable, could potentially prevent multiple problems in the family.

The voices of the fathers in this study, when asked, are expressing their mental health needs loudly. As we will describe in the Recommendations section, integrat ing mental health evaluation and referral for fathers into the Obstetric service may increase the likelihood that fathers will want to seek needed mental health services.

3.4 Perceptions of the Father-Friendliness of MGH Obstetric Services

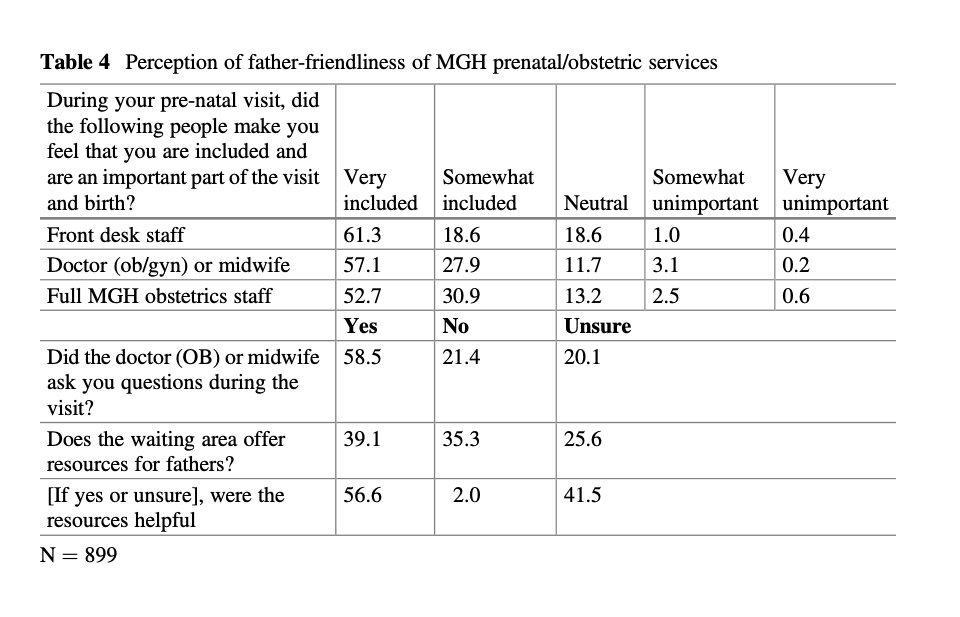

3.4.1 Results

One of the goals of the Father Survey was to determine the current experience of fathers in the MGH Obstetric Services as they accompanied their partners and wives to prenatal visits, analogous to a continuous quality improvement effort, and one of the justifications for the department’s support of this study. We were interested in learning directly from fathers about what areas of the service and the interpersonal experience needed to be addressed to help it become more father and family friendly. Our Father Survey is perhaps the first time men visiting prenatal care have been asked how they were treated (Table 4).

Overall, fathers perceived their welcome and inclusion at MGH Obstetrics pre natal care services very positively, though there were some notable indications suggesting needed improvements. While there was some slight variation across the various specific staff roles, between 57.1% and 61.3% of men reported being made to feel both very included and very important during the prenatal care visit, with an additional 18.6–27.9% somewhat included and important. Between 15 and 20% of men explicitly noted their neutrality or dissatisfaction with an individual obstetric provider or service.

Second, strikingly, large numbers of fathers were not asked (21.4%) or weren’t sure (20.1%) they were directly asked, a single question by an MGH Obstetrics staff member during their partner’s clinical encounter, representing clear missed oppor tunities for greater father engagement.

Third, at the time of our father survey, MGH Obstetrics Services did not offer any written or media resources specifically directed at fathers in the waiting area. Despite that fact, 39.1% of fathers incorrectly reported that they were offered such resources. Of those who said that MGH did offer resources, 56% felt that they were very helpful and 42% somewhat helpful. These findings perhaps reflect some positive patient satisfaction bias. Fathers also may have equated information for mothers with resources for themselves.

3.4.2 Results Discussion

The study results suggest that overall, fathers perceived that they were very well treated at MGH Obstetric prenatal services; they felt included and an important part of their partner’s prenatal care visit—despite the widely remarked on observation in the literature that men often feel excluded from reproductive health services (Steen et al. 2012). No single staff role stood out for engaging men.

There are several reasons, however, to be cautious in over-interpreting the very positive overall paternal responses. First, the MGH Obstetrical Services may already be especially father-friendly, and its providers may be at their father-friendliest when we are conducting our fatherhood survey. Second, most surveys of clinical care provider satisfaction generally reveal very positive responses. Third, maybe the fathers had very low expectations of involvement in their partners’ prenatal care services, which historically are not usually directed at them, beyond being welcomed and treated courteously. And fourth, men may be very reluctant to say anything too critical that might reflect negatively on their partner’s important upcoming delivery care.

Yet, there were also clearly some indications of missed opportunities for service improvement and greater paternal and family engagement. First, despite the fathers professed satisfaction with the prenatal care visit, when asked objectively about their own informational and skill development needs, substantial numbers indicated a desire to receive information about a wide range of fatherhood and reproductive pregnancy topics not currently being provided them at these visits. (See next section, 3.5.) Secondly, at MGH, when the study began, fathers were not represented and mirrored in the waiting area. There were no pictures of men as fathers on the waiting room walls, nor targeted brochures for them, nor any special explicit fatherhood focused prenatal care activities or programs. Third, a small but sizable number of the fathers explicitly noted their neutrality or dissatisfaction with individual obstetric providers or services. And finally, some of the fathers added written survey com ments indicating that they wanted more involvement and were aware of not being included. Others were simply pleased to be recognized and treated as though they mattered through the attention of the Father Survey. (See Sect. 3.6.)

These perceptions of the Obstetric Services friendliness and opportunities for practice improvements are potentially readily remediable. In the subsequent Rec ommendations section, we propose several ways that an Obstetric Service can potentially provide father-specific resources during their partner’s prenatal care visit.

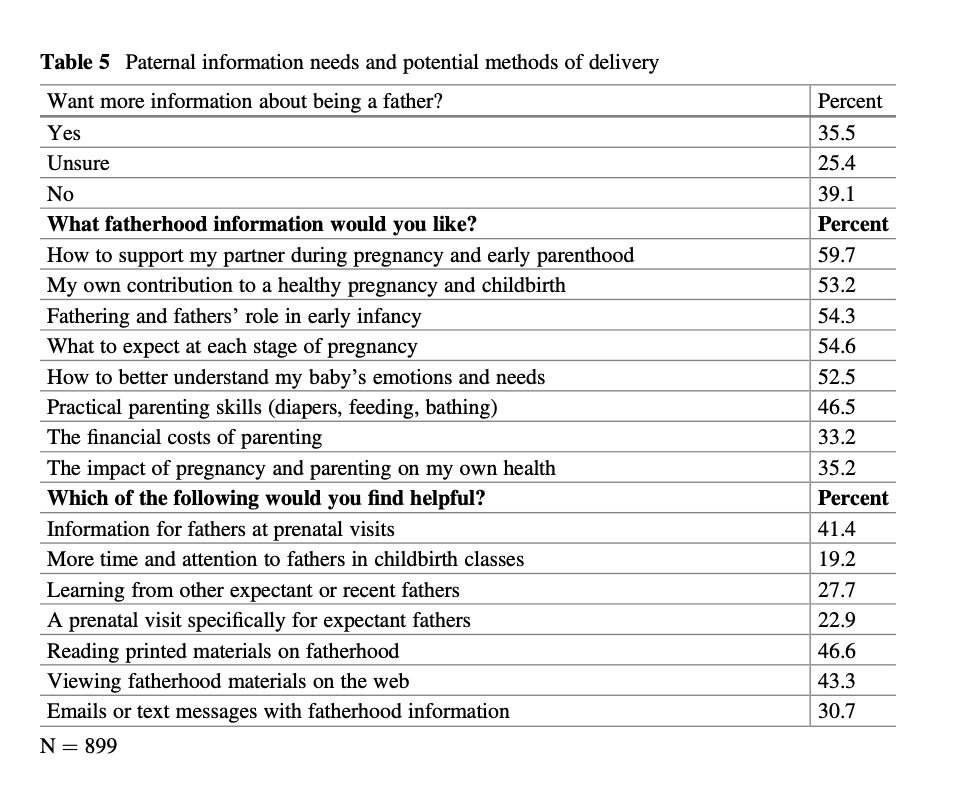

3.5 Paternal Information Needs and Potential Formats for Delivery

3.5.1 Results

The fathers report a balance of confidence and of recognition of needing more skills. Although only 35.5% of fathers initially said they wanted more information about being a father, (25.4% unsure, 39% no), it is clear that as more specific content areas were presented in the Father Survey, more fathers (33.2–59.7%) acknowledged the need for information topics and skills that they could potentially learn (Table 5).

Specifically, fathers were most interested in how to support their wives and partners prenatally (59.7%), and in learning about the stages of pregnancy (54.6%). They expressed strong interest in learning about their role in infancy (54.3%) and about their baby’s emotions and needs (52.5%), both suggesting that fathers plan to be on the frontline of caretaking. Fathers also wanted to know more about their contribution to healthy pregnancy and childbirth (53.2%). Plus, 46.5% stated they wanted to learn more about practical parenting skills. Fathers were relatively less interested in specialized father topics of finances and paternal health impacts. There was a relatively similar distribution of responses between first-time and experienced fathers (data not included).

The fathers most preferred methods for receiving desired paternal information is through written materials: publications (46.6%) or social media (43.3% on the web; 30.7% via texts), though similar numbers (41.4%) also desired this information from health professionals at the prenatal care visit. Fathers desire more reproductive health and fatherhood information and skills at prenatal visits (41.4%) from across a wide range of fatherhood-related topics. Study participants were currently much less interested in direct experiential sharing modalities. These results are similar to other studies of father’s information method preferences (DeCosta et al. 2017).

3.5.2 Results Discussion

Fathers’ voices clearly inform us that they desire more parenting skills and knowl edge, suggesting that they want to participate more actively and knowledgably in the pregnancy and beyond. We believe that most fathers are unaware of the multiple areas of potential and complex learning needed to effectively interact with and care for their infants, as they have not been historically socialized to care for infants and children. Seeing the list of possibilities mentioned in the Father Survey excited fathers’ interest for specific topics.

We believe that the fathers’ requests for more specific fatherhood information and skills prenatally is a further indication that their attitudes toward reproductive health, their parental roles and responsibilities, and child development are in the process of significant cultural transformation; i.e., that we are witnessing a new era of increased paternal commitment to caretaking roles and potentially a stronger emotional engagement with their families and infants.

Currently, there is very limited information directed at fathers here at MGH Obstetric Services, nor likely elsewhere at other Obstetric Services. Like mothers, fathers are clearly desirous of similar prenatal information, and usually are less familiar with it. That 35% of fathers had no known person or places to go to for fatherhood motivational encouragement and information further emphasizes the potential importance of prenatal care visits as a realistic site to learn more about fatherhood.

3.6 Father’s Assessment of the MGH Fatherhood Prenatal Care Initiative

3.6.1 Results

Free Form Father Quotes from the Father Survey

- “I strongly think that obstetrics should increase fathers’ involvement during pregnancy. Thank you for doing this. It’s about time obstetrics involve fathers. Thank you again.”

- “Love the way you guys are thinking. Incredibly impressed with MGH and proactive initiatives like this.”

- “I’m excited you are even asking these questions!”

- “It’s a wonderful experience.”

- “Very good initiative. I’m proud to be a father.”

- “Would be nice to see if system also considers and recognizes fatherhood equally important!”

- “Try to include them (fathers) as much as possible and explain how important they can be to both the mother and baby throughout the pregnancy and childbirth.

In addition to these comments, one father said proudly to his wife that his conver sation with one of the study’s primary investigators was “just for daddies.” And another returned with twins, one on each arm, 4 days after their birth, asking if he could finish the second half of the Father Survey.

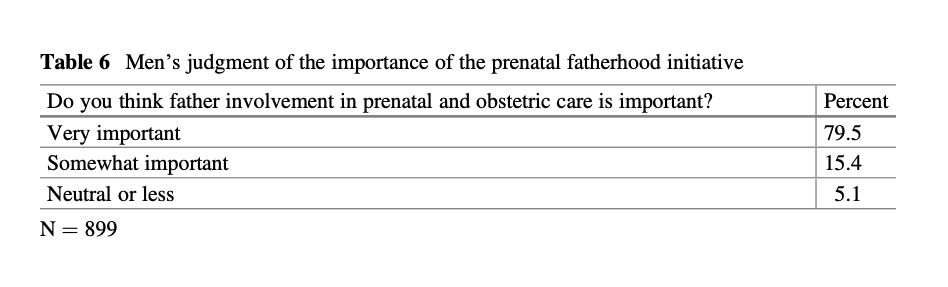

Fathers overall were very supportive of this initial MGH fatherhood prenatal care study, with over 86% agreeing to participate in this baseline fatherhood survey. The fathers who responded to our survey were very enthusiastic about the involvement of men in prenatal and obstetric care: 79.5% thought the initiative was very important, 15.4% somewhat important (combined 94.9%), while only 5.1% thought it was of neutral or lower importance (Table 6).

3.6.2 Results Discussion

The very high rate of survey completion and the general positive and cooperative affective tenor of the fathers both indicate that the fathers were pleased to have interest and attention during their prenatal visits. Indeed, just hearing fathers’ voices and perspectives in prenatal care is already an initial form of positive inclusion.

Overall, these findings suggest that fathers no longer think of themselves as merely chauffeurs to their partner’s prenatal visits, but as active participants in the support to their wives and partners during the birth process and childcare. Their voices are actively requesting support toward these goals. This evolution of men’s paternal interests far surpasses what Obstetric Services currently are aware of and have planned for. Programmatic changes in Obstetric Services to enhance father inclusion could help improve reproductive outcomes and men’s own health and early family involvement.

4 Discussion

The fathers’ very positive response to this study’s survey should help further refute any notions that fathers are relatively unaffected or disengaged by the pregnancy; that pregnancy is not a family event; that they are not present at reproductive health services; that they have limited interest in prenatal care services; or that they will not participate in reproductive health services research. The men in our study were highly engaged, curious, and eager for prenatal involvement and information and skill acquisition.

Specifically, this study documents:

- that men have come of age as frontline, engaged fathers who expect themselves to be actively involved with their partners during the prenatal and birth process. Engaged fathering is the new norm and reflects an expansion of men’s identity.

- that the prenatal period is also marked by substantial paternal physical and mental health needs. This period reveals elevated paternal obesity, insufficient family planning, and lack of primary care health services. Fathers are also burdened with substantial paternal stress, elevated depressive symptoms, and personal isolation.

- that fathers perceive they were made welcome and included by professional staff during their partners prenatal care visits, though many men (~40%) were not asked a single question at the prenatal care visit and no targeted fatherhood resources, information, or services were offered them.

- that fathers desire more fatherhood information and skills training at the prenatal care visit—across a wide range of fatherhood-related topics—which they would prefer to receive from publications, social media, online education or health professional counseling rather than through experiential fatherhood sharing modalities.

- that fathers demonstrate an active and engaged “voice” during prenatal care, and are strongly supportive of initiatives, like at MGH, to enhance their involvement in reproductive health services.

- and finally, that men are willing to participate directly in research and surveys about fatherhood, and that the important and unique information they provide (fathers’ voices) can serve to help develop interventions that foster earlier and more enhanced paternal involvement and engagement in reproductive and child health care, family-centric pregnancy and childbirth, and men’s own health and health care.

The Father Survey findings detailed above potentially reflect major changes in male identity in which fatherhood responsibilities are becoming more important and have expanded to become a broader and deeper part of fathers’ psychological life. Fathers now more often include their nurturing capacity and the development of a bond and emotionally engaged relationship with their children as part of their parenting role. Fathers’ self-esteem, anxiety, pleasure, and sense of responsibility are extended to various fatherhood pursuits. Perhaps this is to be expected as families often have two adults working and sharing parenting duties, placing fathers in frontline caretaking roles.

5 Father-Friendly Obstetric Prenatal Care Practice Recommendations

From its conception, The Fatherhood Project sought to build a collaboration with staff at MGH Obstetrics, to address men’s involvement with fatherhood in the prenatal period and to assess the widely held view that Obstetric Services were not father and family friendly. The Fatherhood Surveys were intended to collect data to provide father-specific guidance to these efforts. As this chapter shows, we believe that we have successfully researched and heard father’s voices at MGH about a set of themes that might lead to enhanced reproductive health services, improved fathers’ health, and increased father involvement with their partners, and ultimately their infants, during prenatal and delivery care.

Based on the fatherhood survey results, an MGH Obstetric Practice Task Force on Fatherhood was created that meets monthly to discuss the implementation of the lessons learned and put them into practice. Based on the joint discussions between The Fatherhood Project and the Task Force, we developed a set of potential practice interventions to enhance obstetric prenatal care and make it more father-friendly and more family-centric, without diminishing the traditional maternal and infant focus of obstetrics. None of the proposed interventions replaces or interferes with existing care or emphasis.

These proposed interventions fall into five broad practice categories that can be conceptualized as sequential steps of increasingly greater father involvement:

- Staff Training about Father Inclusion

- Father-Friendly Clinic Environment

- Explicit Affirmation of Father Inclusion

- Development of Educational Materials for Fathers

- Specialized Father-focused Reproductive Health Care Initiatives

5.1 Staff Training About Father Inclusion

5.1.1 Rationale

Currently, many obstetric staff may not think of father inclusion as a practice goal and may not be comfortable interacting with men (Davison et al. 2017). Over 40% of fathers in our study said no questions were directed at them during their partner’s prenatal visit. Staff training can offer new approaches to including men in the obstetric practice.

5.1.2 Recommendations

- At the practice level, we believe that consistent nursing and clinical staff training that emphasizes the importance of relating to fathers is important for enhanced fatherhood involvement. Training of Obstetric staff by fatherhood experts has the potential to influence providers to talk with fathers regularly and directly during visits and to overcome implicit and explicit biases about fathers as fully compe tent caretakers.

- Formal presentations and father engagement trainings need to emphasize the research-based, improved emotional, social, behavioral, and academic outcomes for children with greater father engagement.

- Training on relating to fathers can help some female staff feel less anxious and more competent when addressing fathers. Since the Father Survey was implemented, The Fatherhood Project conducts an annual fatherhood staff train ing for all nursing and nursing-associated staff in the Obstetrics Department.

- Reaching beyond the practice site is recommended as well. Critical staff training can start earlier at provider educational institutions. Obstetrics can be taught with an inclusive attitude toward fathers in medical, nursing, and midwife programs. Knowledge about the improvement in reproductive health when fathers are engaged in the prenatal period should be emphasized.

5.2 Father Friendly Office Environment

5.2.1 Rationale

Many men don’t feel comfortable in clinical settings for women’s reproductive health services or prenatal care (Steen et al. 2012).

5.2.2 Recommendations

- The waiting area can display photographs on the wall that reflect all configura tions within families, including fathers with babies, which will communicate inclusion and importance.

- An educational video that includes fathers and discusses the critical areas of prenatal and infant care can be running in the waiting room.

- There can be educational materials specifically directed at fathers—pamphlets and magazines—that focus on topics related to fathers’ role in the prenatal and early postnatal period.

- A chair for a second adult or father can be routinely provided in all exam rooms.

5.3 Explicit Affirmation of Father Inclusion

Rationale: Men are hesitant to enter into what is widely perceived as a woman’s traditional world (Johansson et al. 2015; Jomeen 2017).

5.3.1 Recommendations

- To make the concept of family-centric obstetric care real, obstetric practices must make it explicitly clear to both the mothers and fathers (or other partners) that they are both wanted and expected to participate in all prenatal services. Inclusion of fathers needs to begin with the first contact with the obstetric clinical service, the welcoming script that nurses use in their initial phone medical evaluation of new pregnant mothers. At the MGH Obstetric Service, fathers or partners are now actively welcomed and expected to attend services, especially the first visit, thereby establishing the norm for his inclusion throughout the pregnancy. Explic itly saying “you and your husband or partner” rather than solely “you” signals to the mother that the orientation of the service is inclusive of the father, partner, and family, contributing to more positive reproductive outcomes. We recognize that this may seem problematic for evaluation of domestic abuse, but this critical information can be ascertained in many ways without excluding fathers from routine prenatal visits.

- Fathers’ information is not generally collected in the obstetric records, except perhaps for his name and insurance status. We propose recording fathers’ infor mation on all enrollment forms and especially in the EPIC-based Electronic Medical Record. This modification would help define the family as a unit of interest and enable providers to cross reference fathers when they are recording information about mothers.

- It would be helpful to document fathers’ and others’ attendance at prenatal visits. Family-centric pregnancy care necessarily would require family-centric medical records, which currently don’t exist—and father’s health records are not ever linked to their child’s records. Frequently, knowing about the father can be helpful to a provider’s service to the mother. We recognize, of course, that waivers of confidentiality would need to be obtained to share this information.

- Prenatal care clinics could conduct annual anonymous (Continuous Quality Improvement) cross-sectional surveys of the father’s perceptions of their experi ences at OB prenatal care services—similar to the second half of the current MGH Fatherhood Surveys—and publicize the results. This would help demonstrate to fathers that the prenatal care practice valued fathers and their opinions.

- To enhance father involvement, when fathers are present in the exam room, nurses, midwives, and doctors should talk directly to them, in addition to the usual conversation between mothers and providers. As we have noted, nearly 40% of fathers didn’t recall being asked any questions during their MGH prenatal accompanying visit.

- Providers can include father-directed information during appointments, i.e., how to support their partners in the prenatal period (highly desired by the men in our study). If fathers are not present at a visit, mothers can be encouraged to have the father come to the next appointment.

- The importance of co-parenting can be highlighted when both parents are present.

5.4 Development of Educational Materials for Fathers

5.4.1 Rationale

There is very limited educational material directed at fathers, in the obstetric office and online (Albuja et al. 2019).

5.4.2 Recommendations

- The fathers’ voices in this study documented the extensive desire for more paternally oriented pregnancy, childbirth, parenting, and partnering information and skills. The MGH Obstetric Nursing Practice Task Force on Fatherhood has encouraged The Fatherhood Project to create brochures for their practice relating to fathers’ interest in their partner’s pregnancy and delivery as well as infant caretaking and development. Over 50% of men in this survey desired more information and skills.

- We recommend that practices also develop father-specific electronic educational materials. For example, practices may want to offer expectant fathers weekly text messages that they can choose to receive. These text messages can contain the kinds of information fathers requested in our study.

- Additionally, obstetric practices that currently have a dedicated webpage for mothers can develop a similar webpage for fathers. The webpage can allow for interactive question and answer responses and address the fathers’ areas of interest. Referrals for coaching, psychotherapy, and medical evaluation can be available through the website. Most fathers indicated on our survey that they prefer to receive information through electronic means. We recognize that a website and text messages can also serve the fathers who are unable to attend prenatal care visits or whose interest would increase with viewing educational materials they are unaware of.

- Experienced expectant fathers or men who recently became fathers could also be engaged in being peer mentors, working individually, or as a leader of a class or support groups. Announcements of these possibilities can be made available to fathers at the time of visits, or by text and webpage.

5.5 Special Father Reproductive Health Care Initiatives

5.5.1 Rationale

Our current survey documented substantial health and mental health needs among fathers in the prenatal period.

5.5.2 Recommendations

- One idea that we strongly encourage and have proposed is the creation of a specific prenatal visit, perhaps named “The Family Visit,” during which the father (or other partner) will be offered an opportunity to speak confidentially with a dedicated professional about his prenatal fatherhood concerns, hopes, and related health and social issues. We conceptualize this meeting possibly in conjunction with the fourth maternal prenatal visit, the lengthy Glucose Tolerance Test (GTT) visit. Fathers would be invited and informed in advance. During this appointment, fathers would have the opportunity to be evaluated for health and mental health related concerns. This can include drug and alcohol use, obesity, financial concerns, anxiety, depression, anger dysregulation, and other, perhaps more severe, mental health issues. Referrals can be made following evaluation.

- Alternatively, some of these father-targeted health concerns could be addressed with an enhanced primary care visit scheduled during the early pregnancy period. However, most primary care visits do not inquire about potential paternity concerns, plus a man-only visit, however good, is less likely to foster a sense of family-oriented pregnancy. A father visit held through the Obstetric Service as described above during the prenatal period that is about the pregnancy and his needs would be more ideal.

In this section, we presented a sequence of five practical and limited cost interven tions to make obstetric prenatal services more father-friendly and more family centric in order to ensure earlier and enhanced fatherhood engagement and experi ences. These suggestions are all responsive to the fathers’ voices that emerged from our Father Survey.

6 Concluding Comments

From the beginning, our Fatherhood Survey was intended as a public health initia tive aimed at gathering fathers’ voices to guide us in the important work of suggesting interventions and alterations in health service delivery at obstetric practices.

This study attempted to hear the direct perspectives and voices of fathers about their experiences and needs during the prenatal period. The results, we believe, have proven to be very informative—for improving fatherhood experiences, men’s health, and the creation of more father-friendly health services. Fathers’ direct voices are critical—for creating new scientific knowledge about their perinatal conditions, for shaping the new emerging more family-friendly clinical programs (such as the prior obstetric practices recommendations), and for developing the political will to help transform current Maternal and Child Health (MCH) services (Richmond and Kotelchuck 1983). We hope it will be one of many such systematic paternal listening efforts across a wide range of MCH programs and policies.

This study further documents the health, and especially the added mental health, needs of men during the prenatal reproductive period. The isolation, stress, anger dysregulation, and depression expressed by the men can be addressed through father-friendly prenatal initiatives for the improvement of reproductive health out comes. As we have suggested, fathers’ voices inspired practice interventions designed to respond to fathers’ needs in the obstetric service without interference with pre-existing care for pregnant women.

We believe that our study results can lead to a recognition that there is a fatherhood revolution hiding in plain sight that needs to be welcomed and supported in obstetric practices around the country. Fathers and fathers’ health are important to their families’ lives and, in this historical moment, fathers have become eager to engage in the reproductive prenatal care period, presumably leading to their greater engagement with their children and families as frontline caretakers and breadwinners.

Hopefully, Obstetric Services beyond MGH will find the study’s new data on men’s reproductive health needs valuable and will implement some of the proposed paternal health service changes, perhaps altered to fit the particular needs of indi vidual practices.

We hope that this descriptive study of fathers’ prenatal “voices” inspires many more similar perinatal research studies to explore men’s impact on infants’, mothers’, families’, and men’s own health. We hope that others will be motivated to develop and create more father-friendly MCH health services. Ultimately, the critical issue is to hear fathers’ voices—and to engage and uplift the millions of interested fathers while improving reproductive health.

References

- Administration for Children and Families (2019) Healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/programs/healthy-marriage

- Albuja AF, Sanchez DT, Lee SJ, Lee JY, Yadava S (2019) The effect of paternal cues in prenatal care settings on men’s involvement intentions. PLoS One 14(5):e0216454. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216454

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2019) Preconception health and health care. https://www.cdc.gov/preconception/index. Accessed 15 Jan 2019

- Choiriyyah I, Sonenstein FL, Astone NM, Pleck JH, Dariotis JK, Marcell AV (2015) Men aged 15–44 in need of preconception care. Matern Child Health J 19(11):2358–2365

- Davison KK, Charles JN, Khandpur N, Nelson TJ (2017) Fathers’ perceived reasons for their underrepresentation in child health research and strategies to increase their involvement. Matern Child Health J 21(2):267–274

- Davison KK, Gavarkovs A, McBride B, Kotelchuck M, Levy R, Taveras EM (2019) Engaging fathers in early obesity prevention during the first thousand days: policy, systems and environ mental change strategies. Obesity 27(4):523–533

- DeCosta P, Møller P, Frøst MB, Olsen A (2017) Changing children’s eating behaviour—a review of experimental research. Appetite 113(1):327–357

- Frey KA, Engle R, Noble B (2012) Preconception healthcare: what do men know and believe? J Men’s Health 9(1):25–35

- Garfield CF (2015) Supporting fatherhood before and after it happens. Pediatrics 135(2):e528–e530

- Garfield CF, Simon CD, Harrison L, Besera G, Kapaya M, Pazol K, Boulet S, Grigorescu V, Barfield W, Lee W (2018) Pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system for dads: public health surveillance of new fathers in the perinatal period. Am J Public Health 108(10):1314–1315

- Gemayel DJ, Wiener KKK, Saliba AJ (2018) Development of a conception framework that identifies factors and challenges impacting perinatal fathers. Heliyon 4(7):e00694

- Johansson M, Fenwick J, Premberg A (2015) A meta-synthesis of the father’s experiences of their partner’s labour and birth. Midwifery 31(1):9–18

- Jomeen J (2017) Fathers in the birth room: choice or coercion? Help or hinderance? J Reprod Infant Psychol 35(4):321–323

- Kotelchuck M (1976) The infant’s relationship to the father: experimental evidence. In: Lamb ME (ed) The role of the father in child development. Wiley, New York, pp 161–192

- Kotelchuck M (2021a) The impact of father’s health on reproductive and infant health and development. In: Grau-Grau M, las Heras M, Bowles HR (eds) Engaged fatherhood for men, families and gender equality. Springer, Cham, pp 31–61

- Kotelchuck M (2021b) The impact of fatherhood on men’s health and development. In: Grau Grau M, las Heras M, Bowles HR (eds) Engaged fatherhood for men, families and gender equality. Springer, Cham, pp 63–91

- Kotelchuck M, Lu M (2017) Father’s role in preconception health. Matern Child Health J 21 (11):2025–2039

- Kotelchuck M, Zelazo PR, Kagan J, Spelke E (1975) Infant reaction to parental separations when left with familiar and unfamiliar adults. J Genet Psychol 126(2):255–262

- Kotelchuck M, Levy RA, Nadel H (2016) Fatherhood prenatal care obstetrics survey, Massachu setts General Hospital 2015: what men say, what we learned. In: Oral presentation at the annual meetings of the APHA, Denver CO, November 2016. https://thefatherhoodproject.org/research

- Kotelchuck M, Khalifian CE, Levy RA, Nadel H (2017) Men’s perceptions during prenatal care: the 2016 MGH fatherhood obstetrics survey. In: Oral presentation at the annual meetings of the APHA, Atlanta GA, November, 2017. https://thefatherhoodproject.org/research

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW (2003) The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 41(1):1284–1292

- Lamb ME (1975) Fathers: forgotten contributors to child development. Hum Dev 18(4):245–266

- Lamb ME (ed) (2010) The role of the father in child development, 5th edn. Wiley, New York

- Lamb ME, Lamb JE (1976) The nature and importance of the father-infant relationship. Fam Coord 25(4):379–385

- Levy RA, Badalament J, Kotelchuck M (2012) The Fatherhood Project. Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. https://thefatherhoodproject.org/

- Levy RA, Khalifian CE, Nadel H, Kotelchuck M (2017) The impact of fatherhood stress on depression during the prenatal period at the intersection of race and SES. Poster presentation at the annual meetings of the APHA, Atlanta GA, November, 2017. https://thefatherhoodproject.org/research

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health (2018) Massachusetts births 2016. https://www.mass.gov/doc/2016-birth-report/download

- Obama B (2014) My brother’s keeper. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/my-brothers-keeper

- Paulson JF, Bazemore SD (2010) Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA 303(19):1961–1969

- Philpott LF, Leahy-Warren P, FitzGerald S, Savage E (2017) Stress in fathers in the perinatal period: a systematic review. Midwifery 55:113–127

- Redshaw M, Heikkilä K (2010) Delivered with care. A national survey of women’s experience of maternity care 2010. Technical report. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, United Kingdom. https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/id/eprint/2548656

- Redshaw M, Henderson J (2013) Father engagement in pregnancy and child health: evidence from a national survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13:70

- Richmond JB, Kotelchuck M (1983) Political influences: rethinking national health policy. In: McGuire CH, Foley RP, Gorr D, Richards RW (eds) Handbook of health professions education. Josey-Bass, San Francisco, pp 386–404

- Rowan ZR (2016) Social risk factors of black and white adolescents’ substance use: the differential role of siblings and best friends. J Youth Adolesc 45:1482–1496. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10964-016-0473-7

- Sarkadi A, Kristiansson R, Oberklaid F, Bremberg S (2008) Fathers’ involvement and children’s developmental outcomes: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Paediatrica 97 (2):153–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-227.2007.00572.x

- Simon CD, Garfield CF (2021) Developing a public health surveillance system for fathers. In: Grau Grau M, las Heras M, Bowles HR (eds) Engaged fatherhood for men, families and gender equality. Springer, Cham, pp 93–109

- Steen M, Downe S, Bamford N, Edozien L (2012) Not-patient and not-visitor: a metasynthesis father’s encounters with pregnancy, birth, and maternity care. Midwifery 28(4):362–371

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) (2019) Results from the 2018 national survey on drug use and health: detailed tables. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Rockville. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHDetailedTabs2017/NSDUHDetailedTabs2017.htm

- Yogman MW, Garfield CF, the Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health (2016) Fathers’ roles in the care and development of their children: the role of pediatricians. Pediatrics 138(1):e20161128